You have an invention…what next?

The SME decision to patent, publish or keep secret

As a decision maker in a SME, you may recognise the scenario of being faced with an interesting innovation developed by your research team and wondering what should be done with the knowledge of this innovation. Should you rush to file a patent application at the nearest patent office? Is there pressure to quickly publish the work for media attention? Perhaps the innovation will provide a competitive edge, but it’s just not economically justifiable. In this article, I hope to explore some of the thought processes that you may use to decide on the fate of the innovation.

The right answer can vary widely depending on the type of organisation and its IP policy (if any). For example, an academic spin-out or SME may have a different criteria and justification relative to big pharma. Here I am concentrating on SMEs. The technologies may be varied, but there will still be common themes and thought processes you can consider.

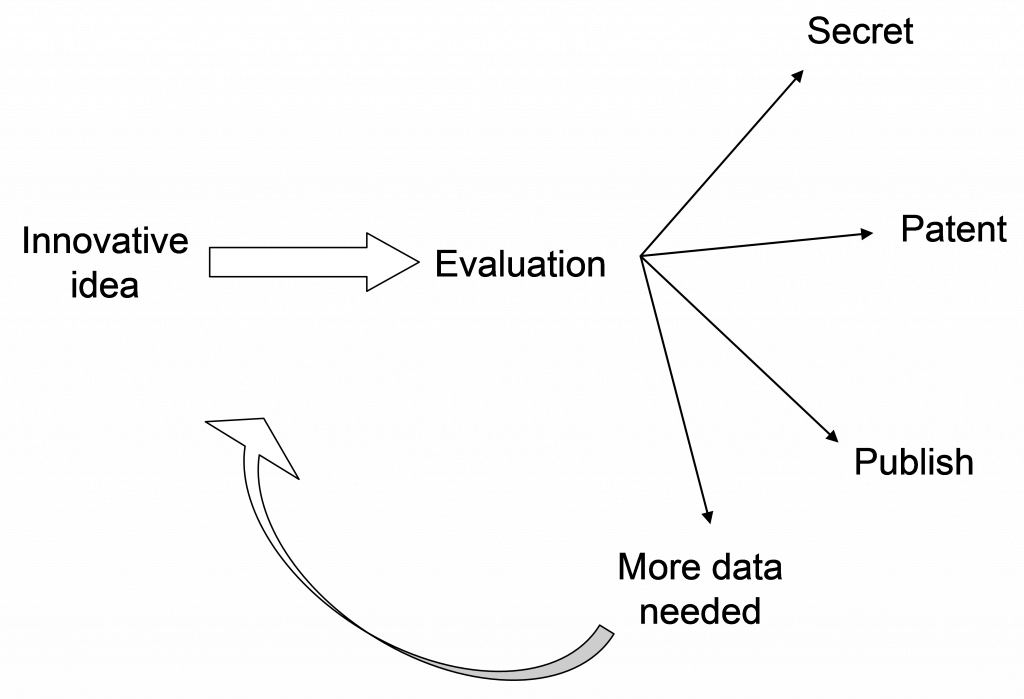

Figure 1.

Figure 1 illustrates an example of a simple thought process for innovation management. The three available options are to:

- keep the innovation secret within your SME, by use of confidentiality agreements;

- file a patent application to patent protect the innovation, and;

- consider the innovation to be non-confidential and perhaps publish the innovation without patent protection.

You may also enter a holding pattern and re-evaluate the decision at a later date, for example if further support data and information are required.

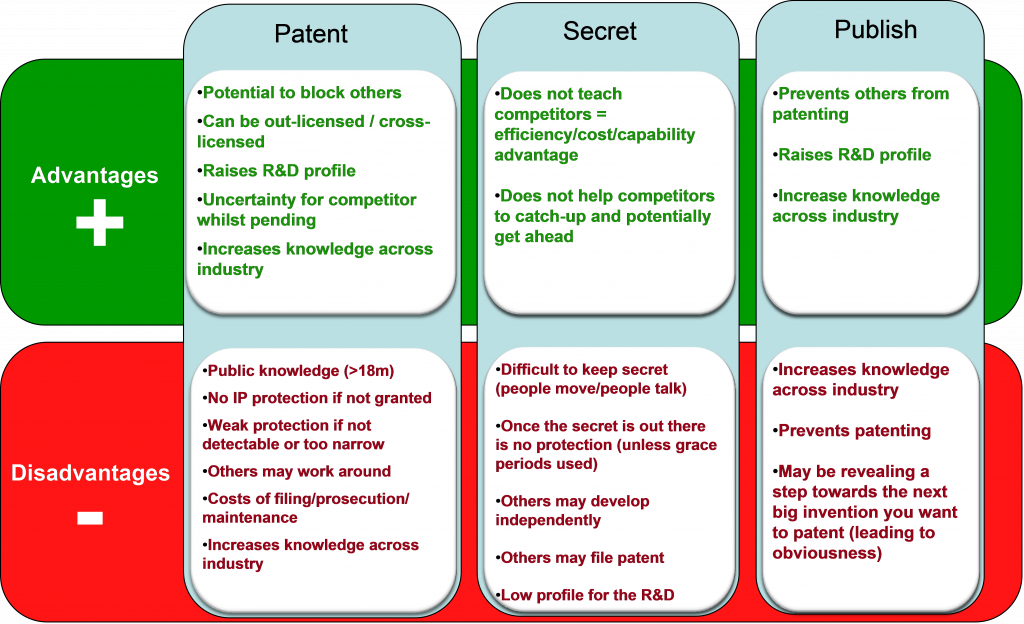

There are advantages and disadvantages to these options for any particular innovation, and Figure 2 provides a sample of such advantages and disadvantages. The relative weight that a SME puts on any one point will largely depend on their IP policy (if they have one) and business model, including their attitude to risk, and the competitive environment in the technology area.

Figure 2.

Each innovation should be taken on a case by case basis. However, as a general rule for a SME wishing to protect their innovations, it may be worth considering all innovations should be filed as a patent application provided that they meet certain key criteria, and of course provided there is budget to do so. If the innovation falls down on any one or more of the criteria then the alternative routes of publication or keeping secret could be the preferred option. An example of how this may work is provided below in a traffic light system where I have provided some suggested criteria that could be considered as a strong direction to file a patent (green light), a potential to file a patent application (amber light), and potentially not worth filing (red light).

Green light criteria

There is a strong direction to file a patent application if all the following criteria are met.

1. The invention is clearly patentable meaning:

i) it has apparent novelty and is sufficiently inventive;

ii) it does not include subject matter such as games, mathematical theory, aesthetic creations, methods of surgery etc.

Your Patent Attorney should be able to assist on these points. Here we can make use of the background knowledge of the inventor to consider if it is reasonable to expect the innovation to be novel and inventive. There is also the option for prior art searching, which could be commissioned before filing a patent application. Alternatively, it can be often cost effective to go straight to filing a patent application and requesting the UKIPO to conduct the search.

2. The innovation is either:

i) essential to the application of the technology; or

ii) optional to the application of the technology but offers a significant advantage.

For example, the invention may be a new modification to a drug molecule that increases its systemic half-life. This may be essential to the efficacious delivery of this drug, or perhaps it offers a significant advantage over existing technology by allowing lower frequency dosing of a patient. However, such an innovation would not pass the green light criteria if it was one of several options that were equally good for extending the half-life and it merely offered an alternative modification that can be used – i.e. it would be neither essential nor advantageous. Depending on the invention there could be some interplay between the advantages it brings over alternatives and its ultimate patentability in terms of inventive step.

3. There is sufficient data

Supporting data can be crucial for a valid patent claim. The claimed invention must be at least technically feasible in the eyes of a skilled person, and preferably this is backed up by actual data demonstrating the invention in practice. The data should demonstrate the benefit or advantages of the invention. Therefore, you should consider if it is the right timing to file an application now with the data you have, or if more data is needed. If more data is needed, you should understand the timeframe for obtaining it, and consider if this fits in with the project timelines and any need to make the innovation public (or talk to third parties).

Your patent attorney can advise on the level of data needed. Many, but not all, jurisdictions allow supporting data to be post-filed as evidence during prosecution. However, this cannot be relied upon to fill major gaps in the support for the claims, which must be supported at the time of filing. For example, a claim to a drug-stabilising formulation requiring a specific polymer could be difficult to achieve unless the polymer was actually demonstrated at the time of filing to increase stabilisation. There is also a risk you would be restricted to claiming only that specific polymer, and not potential variants or alternatives in a class of polymers unless there is data showing at least some other members of the class of polymers having the inventive stabilising effects.

Amber light criteria

If there is a question in regards any of the following ‘Amber light criteria’ you may or may not wish to file a patent application at this stage or at least not until more development has been done.

1. Questionable novelty and/or inventive step

Is there any evidence that your invention is already known? This is termed as ‘prior art’ which may be close, but you may consider it is worth fighting for. Perhaps having a patent application on file is more important at this stage, due to funding requirements, licencing opportunities, or simply keeping the competitors guessing. You may know that achieving a valid patent in several years could be difficult, but there is still value in trying and having an application on file.

2. There is questionable supporting data.

As above, can a patent be filed now with the data you have?

3. Lack of a detectable footprint

The innovation may be clearly patentable, but can any infringement be readily detected? Clearly a new innovative product or a composition can be identified, but what about an innovative process? Does the innovative process leave a mark or signature in the eventual product that could be sold by a competitor? Is it worth patenting if you can’t detect infringement? Perhaps it is the only known way of producing a product. Therefore, the offer of a product from a competitor could be worth investigating as an infringement.

4. Breadth of applicability

Is it worth patenting something that has only a limited market and use? For example, the innovation may be a new digital thermometer component for a specialist scientific thermometer used by a dozen scientists on expedition to the Antarctica only once a year. Alternatively, it may have broader applicability and be useful in every commercial and domestic thermometer produced. The value of the patent protection would be very different in these scenarios.

6. Breadth of claims possible

In the light of known prior art, can you still achieve patent protection that has sufficient breath to make it commercially viable? For example it may be worth patenting a process which relies on a 40-60°C incubation step for a significant advantage, but not if the prior art would force a limitation of the claimed step to 45°C and the competitors can simply use an alternative range of 46-60°C to achieve a similar advantage. Unfortunately, this may only come to light after a rigorous patent examination process.

Red light criteria

You may wish to consider an alternative strategy such as publication or keeping secret if one or more of the following criteria are in place.

1. It is clearly not patentable.

2. It is not advantageous, e.g. it is simply an optional feature bringing no real benefit.

3. No data is available or achievable in a reasonable timeframe.

4. You have no means of accurately detecting infringement.

5. It has very narrow applicability.

6. Only narrow claims are achievable – easy to work around by competitors.

To publish or keep secret?

Once the patent application route is ruled out, you have to decide on whether to keep the innovation confidential (i.e. typically known as ‘know-how’ or ‘Trade Secret’), or to tell the world by publication, or by release of the product or service. Again, there are pros and cons which have to be balanced on a case by case basis and the weight of each factor may be different for various SMEs or technology areas.

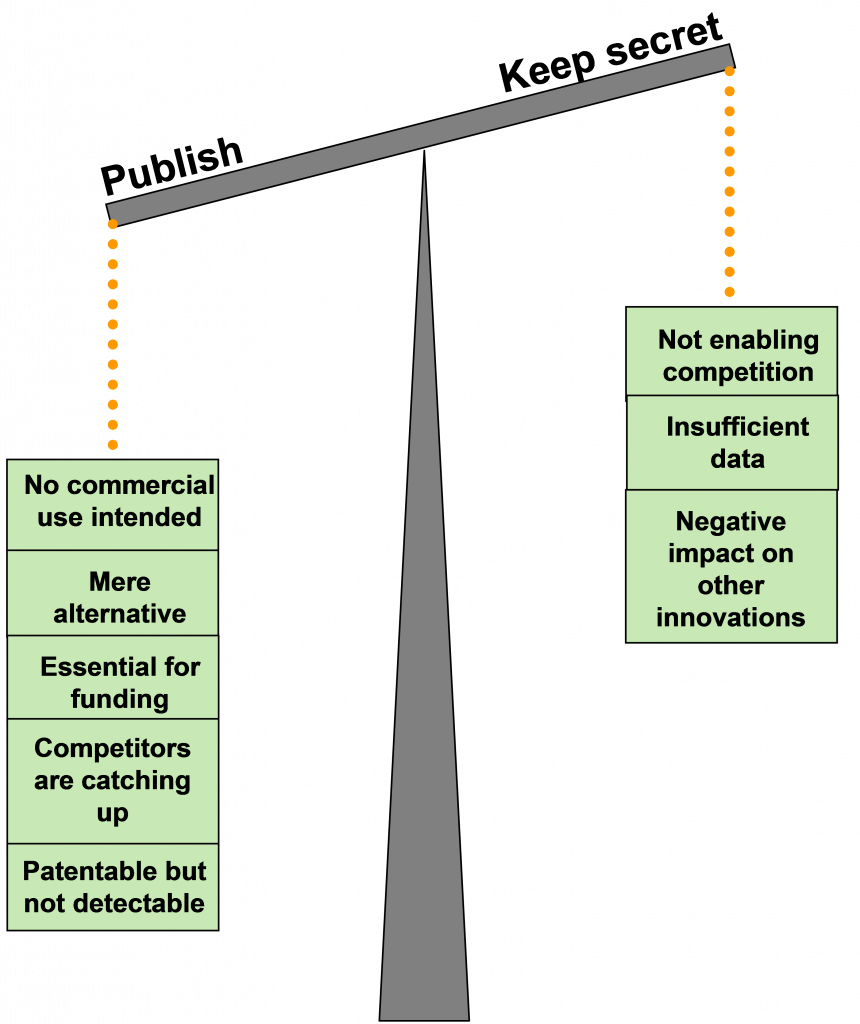

Examples of the pros and cons for keeping the innovation secret are provided in Figure 2. Additionally Figure 3 illustrates how some criteria may tip the balance in favour of either publication or keeping it secret, depending on your business needs. For example factors that suggest a publication of the innovation may be advantageous could be that you wish to avoid others from trying to patent the innovation, ensuring that you will have freedom to operate. There may be no commercial use of the innovation and you may simply want to further the knowledge in the field. Publication of the innovation may be encouraged if marketing is important for sales or investment, unless there is a significant reason to withhold it, such as awaiting results of a study that could impact the patent assessment criteria. It may be in your interest to hold onto data for years until the final form of the product/service is ready for the market. Additionally, are there potentially other innovations in other projects that you could cause to become more obvious if you publish on the present innovation?

Figure 3

Summary

The above criteria and thought processes may not be exhaustive, but they highlight areas for consideration when an innovation hits your desk, and there are competing politics on the eventual fate of the intellectual property surrounding the innovation. Barker Brettell LLP’s patent attorneys have both a broad range of experience and deep understanding of a number of technologies. We can assist with the assessment of many of these ‘patenting criteria’, such as forming initial or in-depth opinions on patentability, assessment of supporting data, and the assessment of the prior art.