Registered Designs: The Lego exception and beyond

Registered Designs are an effective way to get some IP protection in place, particularly in cases where the bar for patent protection may be too high or costs may be prohibitive. In the UK and EU, this works as a ‘registration’: neither the UKIPO nor the EUIPO fully examine the design. However, in order for a design to be enforceable it needs to be valid.

For a Registered Design to be valid in either the UK or EU, it needs to be new and have ‘individual character’. Additionally, Registered Designs cannot subsist in features which are ‘solely dictated by their technical function’ or where features of appearance of a product must be reproduced exactly to connect to, be placed in, around or against another product so that either product may function (the ‘must fit exclusion’).

The Lego Exception

There is an exception to the must fit exclusion and the technical function exclusion, often referred to as ‘The Lego Exception’ or the ‘modular systems exception’. Features of a design that ‘serve the purpose of allowing the multiple assembly or connection of mutually interchangeable products within a modular system’ are registrable and not excluded.

This principle has been tested recently before the General Court of the CJEU in case T-537/22.

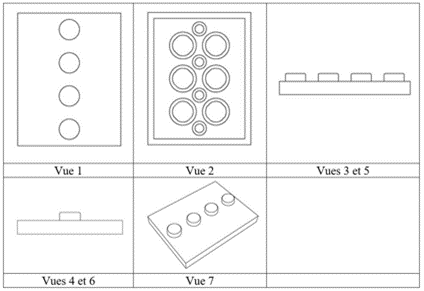

In 2010, Lego® filed Registered Community Design 001664368-0006 for “building blocks from a toy building set”, as shown below.

An invalidity action was applied for by Delta Sport Handelskontor GmbH (‘Delta’). After several rounds of appeals, the case was heard by the General Court of the CJEU (the GC).

Delta submitted that the design should not have been eligible for the modular systems exception because the smooth surface of the Lego brick was not a feature covered by the must fit exclusion. That argument was rejected. The GC found that the modular exception can still apply to those features which are covered by the must-fit exclusion, even if there are features which are not. The GC also stated that if at least one feature of the design can be protected then the design is valid, even if it is only protectable due to the modular systems exception.

Delta also alleged that the earlier Board of Appeal should not have applied the modular systems exception to the design as a whole, and only on the features of interconnection. These features must be new and have individual character. They argued that the burden lay with the holder of the contested design to prove that the modular systems exception was met in this case. However, the GC confirmed that this would contradict the registration-style system of the Community Designs regulation. Delta also failed to substantiate their allegations that there were earlier designs that rendered the Design invalid. The GC dismissed this, and indicated that the disclosure of an earlier design requires demonstration and cannot be considered to be a ‘well-known fact’, even if products in which a design applies to would have been present on the market for a long time and would be generally known to the public.

Alternate designs and the possibility of multi-coloured appearance

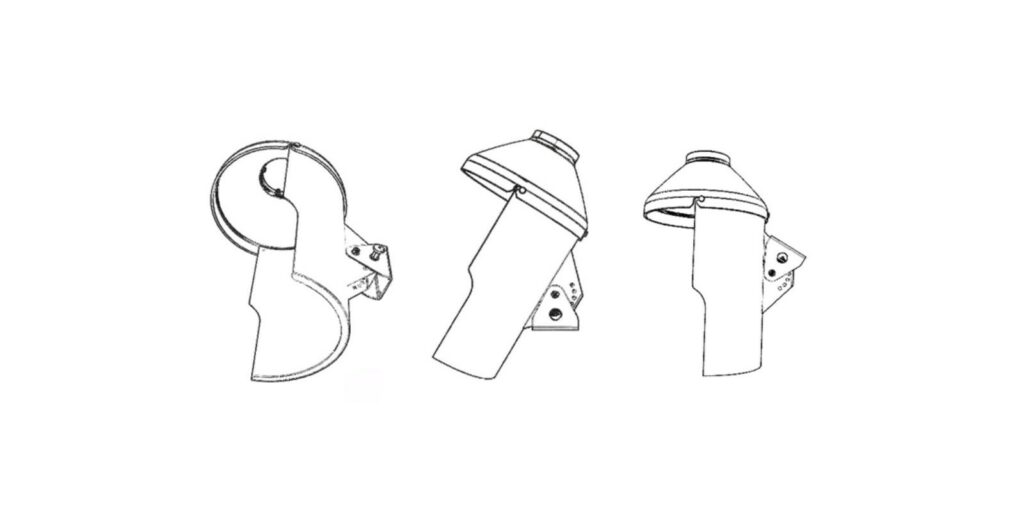

Sprick GmbH Bielefelder Papier- und Wellpappenwerk & Co (‘Sprick’) registered a Registered Community Design for a packing paper dispenser in 2012. Another company Papierfabriek Doetinchem BV (‘Papierfabriek’) was alleged to have infringed, and the claim was taken to court in Dusseldorf alongside a counterclaim for invalidity.

The design was originally found to be valid and infringed. This decision was overturned on appeal by the Higher Regional Court. That appeal decision was then overturned by the German Federal Court and referred back to the Higher Regional Court. This prompted the Higher Regional Court to refer three questions to the CJEU on the technical functions exclusion. The three questions (in brief) were:

1. …with regard to the aspect of the existence of other designs, what significance is attached to the fact that the proprietor of the design also holds design rights for numerous alternative designs?”

The CJEU held that multiple factors must be considered when determining if a design is ‘solely dictated by technical function’. These included features of appearance, the existence of alternative designs which fulfil the same technical function, and the fact that the proprietor of the design in question also holds design rights for numerous alternative designs. They held that this last factor is not decisive for the application of that provision and should be taken alongside other considerations. If it was decisive, then the existence of alternative designs fulfilling the same function as that of the product registered would provide the holder of the design with the exclusive protection of that function in a similar manner to a patent, without having to clear the (higher) bar for patentability.

2. Is it necessary to take into account the fact that the design allows for a multicolour appearance in the case where the colour design is not, as such, apparent from the registration?

The CJEU held that the fact that the design of that product allows for a multicolour appearance “cannot be taken into account in the case where that multicolour appearance is not apparent from the registration of the design concerned”. The possibility of a multicolour appearance allowed by the two-part configuration of the product is subjective if that multicolour appearance does not appear itself in the graphic representation of the design. The purpose of the representation is to define the design, in order to determine the precise subject of the protection afforded by the registered design. If ‘possibilities’ start being considered where there is no indication in the design, then legal certainty is undermined.

3. If the answer to (2) is yes, does this affect the scope of protection of the design?

The answer to (2) was no, and so the CJEU did not consider Question (3).

The two cases show that Registered Designs can still be a useful option for protecting functional products, but at least some non-functional features must be incorporated. Further, the representations filed must reflect the designs to be protected – it is not sufficient to rely on the possibility of a multi-colour appearance, for example. It is worth noting that decisions from the CJEU are not binding on the UK courts but they can be persuasive and, in general, designs cases tend to align between the two.

For more information on protecting your product with Registered Designs, contact the author, one of Barker Brettell’s dedicated Designs and Copyright team, or your usual Barker Brettell Attorney.